Image

The presentation Willpower and powerlessness by artist Peter Zegveld is part of Ars longa, vita brevis, a collection exhibition now on show in Rijksmuseum Twenthe. For Ars longa, vita brevis nine contemporary artists have each installed their own exhibition room around the theme ‘la condition humaine’, or the human condition in all its ambivalence. For this, they have combined their own work with a personal selection from the multi-faceted collection of Rijksmuseum Twenthe.

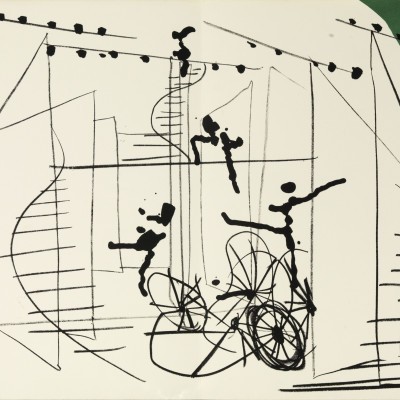

Artist Peter Zegveld has chosen the theme Willpower and powerlessness. For his room he has combined his kinetic installation Die Treppe with a series of lithographs by Constant from the RMT-collection.

We want to build cathedrals, we want to conquer mountain peaks, in the fight we want to push ourselves to the limit for the good cause. In man resides the ambition to transcend himself and take control of life. The Babylonians were already gripped by this urge as the painting The Tower of Babel from the RMT collection shows. They wanted to build a tower which would reach to heaven, but God mercilessly punished the Babylonians for their ambitions. From one day to the next they all started to speak different languages and they were no longer able to work together.

The hubris or pride of the Babylonians was punished by God. Our pride is often punished by life itself. No matter how hard we try, sometimes we reach through our actions the opposite of what we want. That is the tragedy of being human. In the installation Die Treppe by Peter Zegveld the ambition to reach the highest step of the ladder coincides with this tragic awareness. Although we have not climbed with the intention to fall, a catastrophic fate feels inevitable.

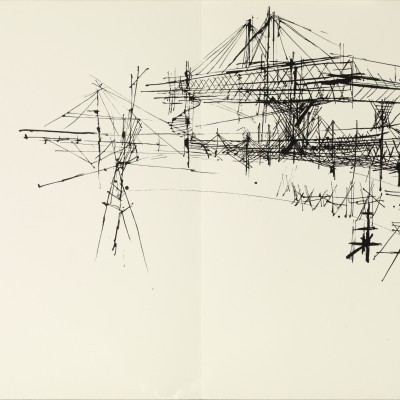

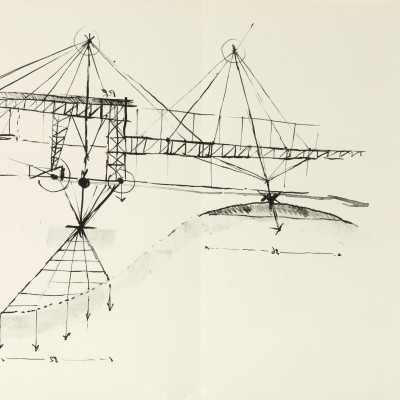

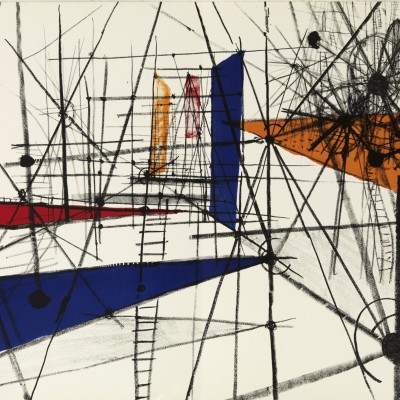

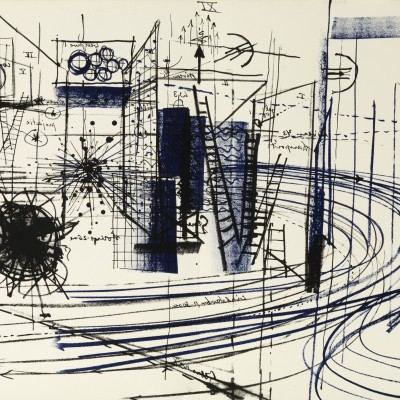

This fatalistic idea stands in stark contrast to the prints of Constant Nieuwenhuys, which are also on display in the same room. The works are part of his utopian project New Babylon, and are caught up in an optimistic belief in a new and ideal society. New Babylon is Constant’s design for the city of the future, but he found his inspiration in the ancient city of Babel. While the Bible criticises the Babylonians for their pride, Constant in fact praises their high-minded culture. For him Babel was the cosmopolitan city of freedom.

In New Babylon too, the focus is on freedom. The city is inhabited by the Homo Ludens: the playing and creative man who is freed from oppressive structures and physical labour. Homo Ludens has given up his existence as a utilitarian animal and shapes his life creatively, through play. On this point, Peter Zegveld and Constant are like-minded, because Zegveld too recognises in play a considerable creative power. For Zegveld, play is a way of approaching his work. His installations are not the result of a premeditated plan. Instead, they arise from experimenting with devices, things and ideas. And Zegveld also plays with the viewer, who he wants to be drawn in by the illusion that is being created on viewing. We see the illusion and we see ourselves. We see a falling man, but the fall is also a new beginning.