Image

Review by Esha Guy Hadjadj in De Groene Amsterdammer of the exhibition New New Babylon at Kunstmuseum Den Haag, 29 March till 31 August, 2025. | 18 June 2025.

For the Dutch article, check the online archive by Fondation Constant or the PDF. Read English translation below.

It is a tension between unadulterated utopia and ominous visions of the future that runs like a common thread through New New Babylon in Kunstmuseum Den Haag.

Esha Guy Hadjadj, 18 June 2025 – De Groene Amsterdammer nr. 25

If it were up to Constant Nieuwenhuijs, everything would be turned upside down. And in the sixties he was certainly not alone in this: revolution was in the air, in Paris there was a rumour that the beach was under the cobblestones and students sprayed texts on the wall such as ‘imagination in power’. That whole rotten world that had produced two world wars had to make way for something new. Constant started a visionary art project, New Babylon: a utopian society in which play and creativity were central. In contrast to the grey and functional housing blocks that rose from the ground during the reconstruction, Constant designed cities above ground level that consisted more of corridors and stairs than of rooms. He was concerned with spaces that radiated movement and connection. In his vision, people would soon be freed from work due to increasing automation and approach life playfully.

What utopian future can we still imagine? A gloomy thought perhaps, but also a common one. It is hard to believe that the best could still be in store now that war, climate crisis and illiberal forces are looming ever closer. That is why the exhibition New New Babylon at the Kunstmuseum Den Haag is so timely. Here, 27 individual artists and collectives attempt to imagine a hopeful future. Entirely in the spirit of Constant’s project, the exhibition offers a diversity of voices and cross-connections between different works.

After the first room, in which you as a visitor are reacquainted with Constant’s art project or are introduced to it for the first time, you come across Mogalakwena by the South African Moshekwa Langa, an enormous three-dimensional ‘drawing’ full of vinyl records, toys, stacks of books and light bulbs, with colourful woolen threads connecting the different parts. The whole thing is somewhat reminiscent of nightlife in a metropolis — although the childish objects also suggest something lonely. It could have something to do with the place where Langa grew up, a place that was not visible on any map from the apartheid era. With his art, Langa asks the question for whom there is room in this world, and how you can nevertheless make a place for yourself when it is not granted to you.

This immediately reveals that New New Babylon is not an unambiguous collection of visions of the future. The first cracks in the utopia are immediately apparent. Next to Langa’s work hang three beautiful photographs by Lebanese Randa Mirza, taken in Beirut. The Lebanese capital has been in an urban planning crisis since the end of the civil war in 1990, with reconstruction going hand in hand with intensive privatization and the disappearance of public space. Mirza photographed the computer-generated posters of planned modernist construction projects in the neighborhood. The posters are peeling or cracked, making the dreamed-of future seem unachievable in advance. In addition, there are the piles of bricks or concrete blocks that lie in front of the posters, which form a contrast with the slick architectural renderings. Mirza thus shows the distance between the project developers and the residents of Beirut and criticizes the increasing social inequality that such construction projects will create.

It is this tension between unadulterated utopia and ominous visions of the future that runs like a thread through New New Babylon, and which sets it apart from Constant’s art project. In the next room, a video artwork by American Steffani Jemison entitled Skybound is on display. The camera is fixed on the blue sky, in front of which flutters a transparent sail with the title of the artwork. Various individuals tell in the voice-over how they decided to fly into the sky one beautiful day. They flew high, over cities, parks and highways, skimming past treetops, and in their voices you hear the wonder and carefreeness of someone for whom existence has finally become light. Skybound is almost unabashedly frictionless.

Opposite Jemison’s film hang photographs by Edwin Zwakman, whose message contrasts sharply with that of Skybound. In his imagination, the Netherlands has largely been flooded and there are multi-storey greenhouses floating on the water, monitored day and night by 3D scanners. At night, the lumbering ships, like glow-in-the-dark oil tankers, radiate bright light colours that should stimulate optimal crop growth. The works succeed in creating an atmosphere that is both seductive and grim, with a future marked by loss and scarcity. We are far removed here from the playful society that Constant envisioned.

The themes that are not found in Constant’s New Babylon are striking. Joshua Serafin and the duo Yamuna Forzani and Céline Hurka explore the contours of a queer utopia in their contributions. The Filipino Serafin tries to use a video performance to hark back to precolonial expressions of gender in order to imagine a possible queer future. Hurka and Forzani try to portray the collective dimension of a more socially just future with a cleverly woven tapestry.

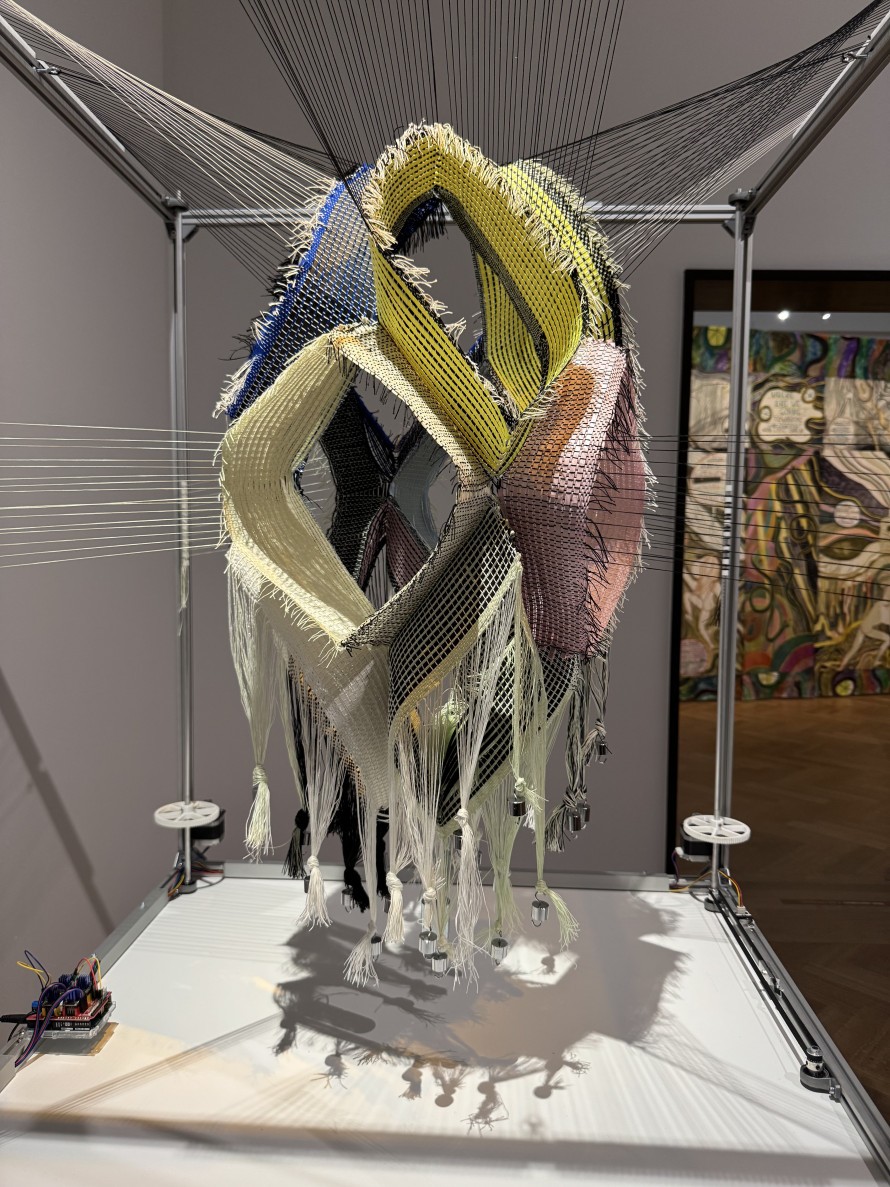

In any case, one is struck by the lack of textiles in Constant’s work when looking at New New Babylon. Strange, that absence, because textiles are ideally suited to emphasise the connection, connection and creativity that Constant wanted to portray. Hella Jongerius shows this beautifully with a moving sculpture made of a loom that looks like a slowly pumping heart. It is incredibly ingeniously constructed, with weights hanging from the sculpture to keep the work tense. Perhaps Constant believed that textile work was simply a form of work that machines would take over. Hurka, Forzani and Jongerius show how textiles are just as capable of stimulating the utopian imagination as architectural models.

Or take the work of Afra Eisma. Like Constant, she creates environments that attempt to offer an escape from the conventional spaces of our lives. But in her work, the soft forces are paramount: playful tufted carpets with cuddly figures in warm colours. Visitors are allowed to sit on the artwork and let themselves be embraced by the strange creatures. On the wall, we see a cheerful scene of alien creatures using the same tufting technique. For Eisma, it is not so much about play as about a desire for security, a response to the cold and businesslike spaces of everyday life.

Constant’s great flight forward seems to make way for a return or flight inward in New New Babylon. The childlike, nature and the spiritual occupy a prominent place in New New Babylon. Emma Talbot’s work focuses on origin myths, with birth as its central theme. Two large canvases with panels show scenes with faceless figures and balloons with texts on them such as ‘why do we think we can outsmart nature, become superhuman and avoid our expiration date?’ Pelumi Adejumo, whose poem 04:04 In the courtyard is split into several panels and playfully distributed throughout the exhibition, also seeks a path to redemption in seclusion.

Thus, New New Babylon does not appear to be a modernist vision of the future in which the malleability of society is paramount. The unbridled creative forces that Constant wanted to unleash in the sixties make way here for more limited and subdued visions that confront us with the limits of what our society can handle. Humility and small-scale play a bigger role, as do the obstacles to a better future.

Jonas Staal shares his first drawings from a multi-year research project that builds on Constant’s New Babylon. Staal is inspired by oil platforms, and by placing photos of Constant’s models next to photos of these platforms, the similarity immediately jumps out. He shows how we can reuse these icons of the fossil industry in the future as green islands that are connected to each other and to the mainland. Staal is perhaps the most faithful to the principles of Constant’s New Babylon, but his emphasis is nevertheless on reusing what is already there. Not everything needs to be overhauled.

The contribution from Werker Collective is perhaps the clearest example of the smaller-scale nature of New New Babylon. The collective shows archive material from activist movements on Amsterdam’s Nieuwmarkt across a long wall. The texts show how multiple social movements meet in this historic part of the city: from the Iranian protests of 2022 to the resistance against the erotic center, with testimonies from Nieuwmarkt residents who experienced the riots of the seventies. They show how the city planners can be stopped as long as residents organize themselves.

But that does not mean that residents can then realize their own vision of the neighborhood. Instead, Werker Collective replaces the concrete utopia with examples of resistance that only hint at a possible other world. Over the long wall we see a decades-long history full of utopian moments, but without a clear plan. A time panorama of the city, not as the fruit of one person’s imagination, but as a continuous play of forces between multiple conflicting interests. This work reminds us that there are always people with a vision for the future, but that the main question is who we listen to.

Photo credits:

— Moshekwa Langa, Mogalakwena, 2018, © Fred Ernst / collectie Kunstmuseum Den Haag

— Emma Talbot, Where Do We Come From, What Are We, Where Are We Going, 2021, © Fred Ernst / courtesy de kunstenaar / Kunstmuseum Den Haag

— Hella Jongerius, Breathing Loom, 2025, © Kim van der Horst